Hurricanes, wildfires, electrical grid outages – wireless carriers have their hands full keeping cell sites on the air.

Last week Hurricane Laura pounded the Gulf Coast. In Louisiana alone, over 200 of its 4,650 cell towers went off the air because they ran out of power. (see, Cell Site Outages Abound in Gulf as Laura Wreaks Havoc).

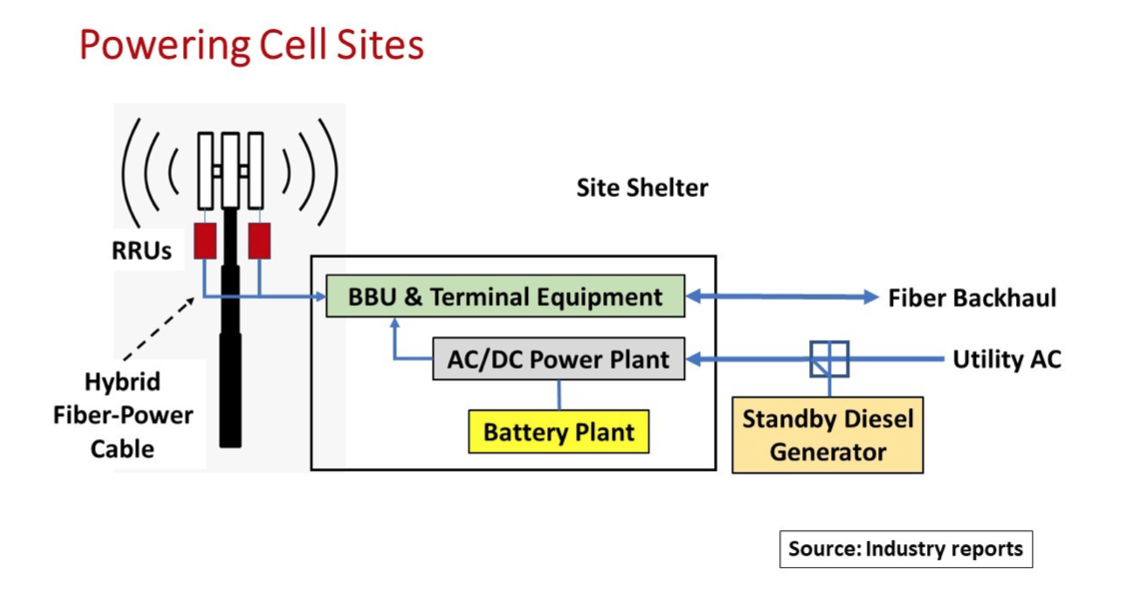

This happens when on-site batteries completely discharge, the standby diesel generator runs out of fuel, or both, before the utility AC power to the site could be restored.

Specialized power plants convert the incoming utility AC power to direct current to run the site electronic equipment, referred to as the load. The power plant also charges standby batteries, either lead-acid or nickel-cadmium, that discharge DC power to the load when the utility AC is interrupted.

The amount of engineered battery reserve time varies with the site location and the load size. Typical cell site battery reserve times are two to four hours.

A standby diesel generator, furnished by the carrier or the tower company, replaces the interrupted AC power input so the site can operate for several days without refueling. Such configurations reduce battery backup requirements, saving cost and space.

How much standby power is appropriate? The issue keeps coming up every time disaster hits without any real resolution.

DC power systems account for 3-4 percent of overall wireless capex and can run 5-7 percent at a cell site, depending on the deployment. Power capex can be significant across national networks of 40,000-50,000 cell sites.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 knocked out about 1,000 cell sites and left millions of citizens along with emergency services without communications for days.

A subsequent FCC investigation determined that failed cell sites were either damaged, flooded or simply ran out of power. On this latter point, the FCC ordered a minimum battery backup of 8 hours at cell sites and 24 hours at switching sites.

The carriers pushed back, citing excessive costs and no FCC authority to mandate such requirements. The courts sided with carriers, allowing them to determine their site backup power reserves.

In 2012, Superstorm Sandy took out 25 percent of cell sites in a 10-state area from Virginia to Massachusetts leaving millions without cell phone service, some for more than a week.

Carrier backup power philosophy has changed little since Katrina or Sandy. Outage problems continue to resurface.

The question is: How reliable and resilient must wireless networks be?

Today, cellular networks are essential services on two counts.

The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show more than 60 percent of U.S. households now have cell phone-only service. Customer expectations of reliable wireless services are growing.

Secondly, COVID-19 brought home the fact that wireless services are not just essential, they are critical for communicating alerts and directives, and with each other, in emergencies.

Wireless networks are designed to handle increased traffic volumes under normal operating conditions. When recent disasters like Hurricane Laura and California wildfires hit, then network operability is tested.

Wireless service providers have options to sustain cell site operation during power outages.

Increased power equipment capex can address the site duration problem. More batteries increase reserve although more site space, and more maintenance, may be needed for additional battery strings.

Carriers are using cell site-on-wheels (COWs) rather than increasing site backup power. For instance, AT&T FirstNet has 75 COWs ready to serve roughly 10,000 jurisdictions across the country when disaster hits. But is that enough?

New IoT remote battery monitoring systems give carriers near real-time status of the battery discharge parameters such as time-to-empty and end-of-life (see, Cloud-based Battery Monitoring Enhances Network Operations). Knowing battery conditions prior to the AC failure, as well as during the outage event itself, allows for carrier staff to make the most informed emergency response decisions.

Wireless carriers could also outsource their DC power to the tower or infrastructure companies.

Though a topic of debate for some time, carriers prefer to control the active equipment at each site. Still, in overseas markets, DC power is part of the Service Level Agreement that tower companies provide carriers.

If U.S. towercos operated a common DC power plant with batteries and generators shared (for an incremental rental fee) among their tenants at a given cell site, then the towercos assume the capex and associated operating expense, and site reliability assurances.

Something worth considering.

By John Celentano, Inside Towers Business Editor

Reader Interactions